With recent news of the Sun having completed a magnetic reversal, the question is often raised about the Earth's own magnetic field. Could our magnetic field undergo a magnetic reversal as well? And could that have serious consequences for life on Earth?

It turns out that Earth's magnetic field has undergone a reversal fairly frequently on a geological scale, but such reversals don't pose a threat to life on Earth.

The magnetic field of the Earth is often portrayed as a large magnet that runs through the center of the Earth, with the magnetic poles located basically at the north and south poles of the Earth, but this is only a rough approximation. Earth's magnetic field is generated in its core. The core of the Earth has a solid central region surrounded by a fluid outer region. This outer region undergoes convection, and its motion generates the magnetic field through what is known as a dynamo effect.

The effect is similar to the way the Sun's magnetic field is generated. For this reason, the Earth's magnetic field (like the Sun's) is not static. Over the past several centuries, for example, we have seen the magnetic field gradually change, and can even observe how the location of the north and south poles shifts over time.

A map of the Earth's magnetic field and its changes over the years. Credit: U.S. Geological Survey.

We know that the Earth's magnetic field has undergone reversals through geological evidence. For example, the Mid-Atlantic ridge is a boundary between tectonic plates that are gradually pulling about at a rate of a few centimeters per year. As they pull apart, magma flows through the fissure to create new ocean floor. When the magma solidifies, its magnetic alignment with the Earth's magnetic field is locked in stone. By measuring the magnetic field of the ocean floor near the ridge, we can observe how the orientation of the Earth's magnetic field has changed over time.

What we find is that over the past 20 million years, Earth's magnetic field has reversed every 200,000 - 300,000 years or so. Because we can observe the changes over time, we also know that these reversals typically happen gradually, over thousands of years. Currently, the Earth is in a period of 'normal' polarity. The latest period of 'reverse' polarity, also called chrons, occurred 780,000 years ago. But there are also brief complete reversals, known as Laschamp events, the last one lasting about 440 years, 41,000 years ago during the last glacial period.

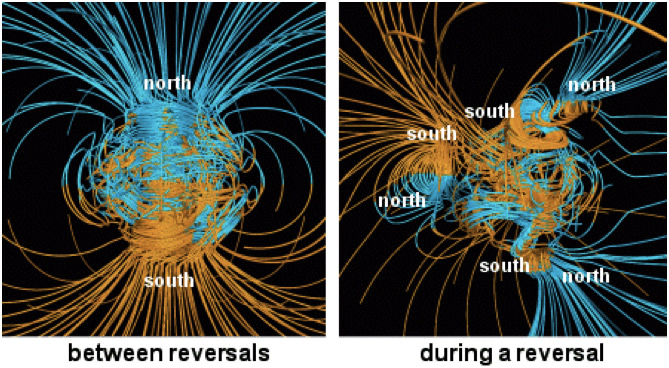

We also know that the Earth's magnetic field doesn't completely disappear during a reversal. Instead, it becomes chaotic during the transition period before settling down again.

NASA computer simulation of magnetic field lines of the Earth. The blue lines point towards the center, while the yellow point away. The densest clusters of lines are within the Earth's core.

Because the Earth's magnetic field provides protection against solar flares and the like, it has been suggested that a magnetic reversal could lead to catastrophic changes in the Earth's ecosystem. But studies comparing magnetic reversals with things like extinction events have found no evidence of the reversals affecting life on Earth in any significant way. At the same time, there are species that depend upon Earth's magnetic field, such as migratory birds and fish, and these could be seriously impacted by a rapid change in our magnetic field, but these effects would be localized, and not catastrophic.

So there's no need to fear a magnetic reversal. Long term it just means we'd need to switch the labels on our compasses.

Read more articles by Brian Koberlein here.