Over four decades ago, Neil Armstrong took his first step on the lunar surface - a very dusty place. At the time, scientists didn't realize just how big the impact of lunar dust would prove to be. The abrasive particles stuck to everything they touched. This caused scientific instruments to overheat and even gave one astronaut - Apollo 17's Harrison Schmitt - a type of lunar dust allergic reaction! The presence of the dust gave rise to a scientific experiment to deduce how quickly it accumulated on surfaces, but over the years NASA's findings began to collect a dust of their own.

Even though it would appear the 44-year-old data was lost, researchers have resurrected the old findings to give us the first figures on how fast lunar dust gathers on surfaces. Unlike its prolifically pesky Earthly counterparts, the sparse lunar particles take their good, sweet time to gather - forming a layer about a millimeter thick every 1,000 years. While that might seem incredibly slow, it's still about ten times faster than scientists originally thought. Even at this snail's pace, it is still fast enough to be considered a potential threat to equipment such as power generating solar cells which may be part of future missions.

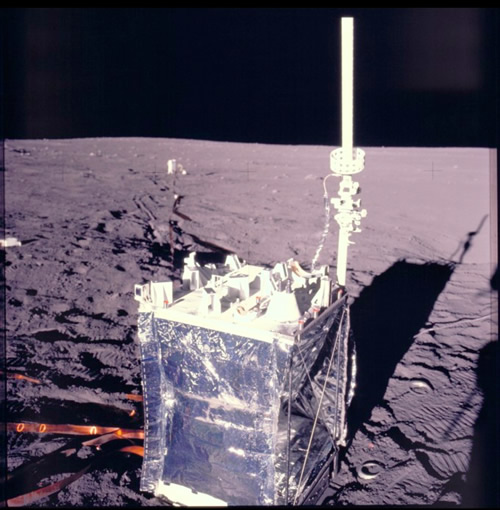

The Lunar Dust Detector, attached to the leftmost corner of this experiment package left by the Apollo 12 astronauts, made the first measurement of lunar dust accumulation. As the matchbox-sized device's three solar panels became covered by dust, the voltage they produced dropped. Credit: NASA

"You wouldn't see it; it's very thin indeed," said University of Western Australia Professor Brian O'Brien, a physicist who developed the experiment while working on the Apollo missions in the 1960s and now has led the new analysis. "But, as the Apollo astronauts learned, you can have a devil of a time overcoming even a small amount of dust."

The faster-than-expected pile-up also implies that lunar dust could have more ways to move around than previously thought, O'Brien added.

While a lunar dusting could be a very big deal, the experimental equipment which involved three Apollo missions was diminutive. To conduct his six year experiment, O'Brien used an arrangement of small solar cells connected to a matchbox-sized case. The tests were simple: measure the drop in voltage as the particles obscured the incoming light. The results: according to the test measurements, 100 micrograms of dust collected over a surface area of a square centimeter in a period of a year. At this rate, it would take about a year to cover a basketball court in a pound of particles.

Just what kind of impact could that have on scientific equipment? By comparing the effects the dust had on the cells from accumulation and from damaging high-energy radiation from the Sun, O'Brien deduced that shielded power supplies could suffer. Their output could be reduced, a situation with even more significance than those caused by a solar outburst. While potential radiation damage was factored into the design of solar cells, no one really gave a thought to a potential dust issue. "While solar cells have become hardier to radiation, nothing really has been done to make them more resistant to dust," said O'Brien's colleague on the project Monique Hollick, who is also a researcher at the University of Western Australia, in Crawley. "That's going to be a problem for future lunar missions."

However, this isn't the first time that NASA took on a housekeeping mission. When Apollo 11 departed the Moon, scientists knew the takeoff would stir up a sizeable amount of dust - dust which would deposit itself on nearby science experiments. Designing a way of circumventing the issue was problematic. Detachable covers would require a way of being removed after the lander left the surface. Everything from a small explosive charge to a robotic removal was considered, but these options simply left more room for errors to occur.

"Then I asked what I thought was a pretty common sense question," recalled O'Brien. "If we've got to guard ourselves against damage from the lunar module taking off, who's measuring whether any damage actually took place; who's measuring the dust?"

Utilizing his eureka moment, O'Brien then invented the Lunar Dust Detector experiment as a small add-on device to the larger experiments. Requiring little power and weighing only 270 grams (0.6 pound), the dust detector reported back to Earth alongside the non-scientific data. "It really got a free ride," O'Brien said.

The housekeeping hitchhikers were part of the Apollo 12, 14 and 15 missions until they were switched off in September 1977 due to budget cuts. Even though the detectors were doing their job, NASA didn't keep the archival tapes of the data the LDDs had collected. For thirty years, NASA just assumed the information was lost. However, in 2006 O'Brien caught wind of NASA's mistake and informed them that he had kept a set of backup copies!

There were three solar cells located in the experiment, each of them covered with a different amount of shielding. Employing his data set, O'Brien took a look at the damage caused to both the shielded and unshielded solar cells. With this information, he could determine that dust - not radiation - was the culprit which caused the most damage to the protected cells. Dust? According to previous modeling, lunar dust was only supposed to come from falling cosmic dust and meteor impacts. "But that's not enough to account for what we measured," O'Brien said.

So exactly where is this dust coming from? Because the Moon has no atmosphere, the regolith should simply remain in place. However, O'Brien said a popular idea of a "dust atmosphere" on the Moon could explain the difference. In this scenario, solar radiation should be strong enough to displace a few electrons out of the atomic dust particles each lunar day. These electrons could possibly build up a small positive charge. During lunar night, electrons from the solar wind could impact dust particles and impart a negative charge. When the illuminated and non-illuminated sides meet, the electrical forces could cause the charged dust to lift from the surface and populate the lunar sky. "Something similar was reported by Apollo astronauts orbiting the Moon who looked out and saw dust glowing on the horizon," said Hollick.

Levitating lunar dust? While it might seem a little far-fetched, it's a concept which could soon be confirmed by NASA's Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer (LADEE), launched in September. The spacecraft orbits 250 kilometers (155 miles) above the surface of the Moon, searching for dust in the lunar atmosphere. While LADEE closely examines the Moon's atmosphere, O'Brien celebrates the science experiment which took many years to complete, but has finally shown a worthy outcome. "It's been a long haul," said O'Brien. "I invented [the detector] in 1966, long before Monique was even born. At the age of 79, I'm working with a 23-year old working on 46-year-old data and we discovered something exciting -- it's delightful."

Original Story Source: American Geophysical Union