- Telescopes

- Solar

- Mounts & Tripods

- Accessories

-

Astrophotography

- Sale Astrophotography

- New Astrophotography Products

- Astrophotography Kits

- Astrophotography Telescopes

- Astrophotography Cameras

- Astrophotography Solutions

- Autoguiding Solutions

- Astrophotography Accessories

- Camera Adapters & T-Rings

- Astrophotography Filters

- Focal Reducers and Field Flatteners

- Video Astrophotography

- Binoculars

- Sale

- Gift Center

- Shop by Brand

{"closeOnBackgroundClick":true,"bindings":{"bind0":{"fn":"function(){$.fnProxy(arguments,\'#headerOverlay\',OverlayWidget.show,\'OverlayWidget.show\');}","type":"quicklookselected","element":".ql-thumbnail .Quicklook .trigger"}},"effectOnShowSpeed":"1200","dragByBody":false,"dragByHandle":true,"effectOnHide":"fade","effectOnShow":"fade","cssSelector":"ql-thumbnail","effectOnHideSpeed":"1200","allowOffScreenOverlay":false,"effectOnShowOptions":"{}","effectOnHideOptions":"{}","widgetClass":"OverlayWidget","captureClicks":true,"onScreenPadding":10}

{"clickFunction":"function() {$(\'#_widget1589658372003\').widgetClass().scrollPrevious(\'#_widget1589658372003\');}","widgetClass":"ButtonWidget"}

{"clickFunction":"function() {$(\'#_widget1589658372003\').widgetClass().scrollNext(\'#_widget1589658372003\');}","widgetClass":"ButtonWidget"}

{"snapClosest":true,"bindings":{"bind0":{"fn":"function(event, pageNum) { PagedDataSetFilmstripLoaderWidget.loadPage(\'#recentlyViewed\', Math.floor(pageNum)); }","type":"scrollend","element":"#_widget1589658372003_trigger"}},"unitSize":220,"widgetClass":"SnapToScrollerWidget","scrollSpeed":500,"scrollAmount":660,"afterScroll":"","animateScroll":"true","beforeScroll":"","direction":"vertical"}

{entityCount: 0}

{"emptyItemViewer":"<div class=\"image\"><!-- --></div>\n <div class=\"info\">\n <div class=\"name\"><!-- --></div>\n <div class=\"orionPrice\"><!-- --></div>\n </div>\n ","imageThreshold":3,"pages":2,"dataModel":{"imageWidth":90,"cacheEntitiesInRequest":false,"dataProviderWidget":"com.fry.ocpsdk.widget.catalog.dataproviders.RecentlyViewedDataProviderWidget","imageHeight":90,"itemViewerWidget":"com.fry.starter.widget.viewers.ItemViewerWidget","direction":"vertical"},"pageSize":3,"widgetClass":"PagedDataSetFilmstripLoaderWidget","loadThreshold":1,"direction":"vertical"}

{"showSinglePage":false,"totalItems":263,"defaultPageSize":20,"paging_next":"Next","paging_view_all":"View All 263 Items","paging_view_by_page":"View By Page","pageSize":20,"paging_previous":"Prev","currentIndex":220,"inactiveBuffer":2,"viewModeBeforePages":true,"persistentStorage":"true","showXofYLabel":false,"widgetClass":"CollapsingPagingWidget","activeBuffer":2,"triggerPageChanged":false,"defaultTotalItems":263}

Even though Starry Night« offers a great system for generating lists of objects to observe, I've personally always found a graphical presentation more useful.

I've never really cared for the 180░ all sky charts which you see in most books and magazines, and which Starry Night« generates automatically. I find the scale too small and the constellations appear distorted. I prefer to generate a set of four larger scale charts, each depicting a quarter of the sky, centred on the four points of the compass and each showing the sky from horizon to zenith.

Let's suppose I want to observe objects from Messier's catalog around 10 p.m. on New Moon night, August 12, from my farm in Coldwater, Ontario. I start by setting Starry Night« to this time and date. On the Options pane, I add the things I want on my chart: the constellation stick figures and boundaries, and the Messier objects. Since I?ll be observing with a Dobsonian, I also turn on the Alt-Az Grid.

The major trick I've discovered is how to generate a chart which includes exactly 90░ from left to right and also from horizon to zenith. Here's how to do it.

First open the pane on the left side of the screen; it doesn't matter which tab you click. Between the pane and the tabs is a very narrow vertical blue strip with a single short vertical line in its middle. This is the handle which lets you adjust the width of the pane, but it also allows you to adjust the dimensions of the viewing window.

Put your mouse on this narrow strip and experiment with dragging it to the left and right.

As you do so, observe what happens in the Zoom window at the far right end of the tool bar. Strangely enough, the "width" dimension stays the same (100░ is the default) while the "height" dimension changes. Adjust it until the two numbers are the same (100░ say) and leave the blue strip there.

Now click on the arrow on the right side of the Zoom box and select 90░ from close to the bottom of the menu. Drag the sky image downwards with the mouse until the two tiny arrows forming a circle appear at the top of the screen. Back up a tiny bit until they just disappear. Your window is now set to display 90░ of the sky from east to west, and 90░ from horizon to zenith.

To get four exact quadrants of the sky facing North, West, South, and East, turn on the scroll bars under the View menu. If you slide the scroll slider all the way to the right of the scroll bar, you will be viewing North. Print this chart with the following settings N.pdf:

- 1 Pane ON

- "Full Sky" Chart (180░) OFF

- Fill page when printing OFF

- Use current settings ON

- Print legend ON

Now click once in the scroll bar to the left of the slider. The chart will now be centred on the Western sky. Print this chart W.pdf. Click again to the left of the slider, and you'll get the Southern view. Print S.pdf. A final click will move the view to the East. Print the final chart E.pdf.

I find charts in this format extremely easy to use in planning my observations. I concentrate first on the objects towards the bottom of the South chart, because these are low in the sky and will never get any higher. Then I look for objects low on the West chart because they too will be setting soon. I can be more relaxed looking for objects on the East chart, and leave those on the North chart for last, because they are mostly circumpolar.

I avoid objects right at the tops of the charts because these are in "Dobson's Hole," the part of the sky hard to reach with a Dobsonian mounted telescope. In an hour or two, these objects will have moved to a more comfortable position.

I use charts like these for all my observations, for example plotting all of the variable stars currently on my observing program. I can prioritize my observations in seconds, and easily see which objects will be conveniently close to each other for observing.

When I was observing the Herschel 400 deep sky objects, I put together a customized Starry Night« observing list of the objects I had yet to observe, and then removed the ones I'd observed each morning after I finished an observing session.

It gave me a sense of accomplishment to see the plotted objects gradually disappear until all were gone, and I'd completed the list!

August 2007

Geoff has been a life-long telescope addict, and is active in many areas of visual observation; he is a moderator of the Yahoo "Talking Telescopes" group.

{ sourceURL:'/catalog/includes/quicklook_miniproduct.jsp?entityId=100264&entityTypeId=4', sourceSelector:'' }

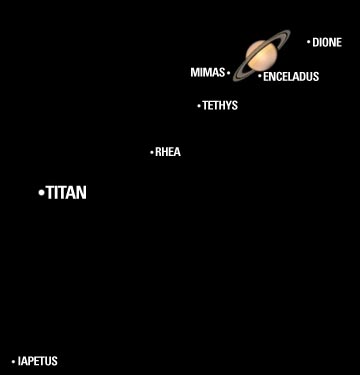

When Galileo first looked through his telescope at Saturn, he thought it had two large companion planets on either side of it. He probably saw something like this:

Once he saw them seem to shrink and disappear, and then return. We know now that Saturn has rings, which looked like large companions in Galileo's small and primitive telescope — and when they seemed to disappear, he was actually seeing the rings edge-on.

This happens every fifteen years, when the Earth crosses Saturn's ring plane. The last such crossing, in February 1996, was relatively easy to observe, as Saturn was setting a few hours behind the Sun at the time. This year we aren't so lucky; on September 4, when we cross the ring plane, Saturn will be a mere 10░ away from the Sun in our sky. It won?t be safe to observe with an Earth-bound telescope.

Fortunately, Starry Night is here to simulate the view:

{ sourceURL:'/catalog/includes/quicklook_miniproduct.jsp?entityId=100329&entityTypeId=4', sourceSelector:'' }

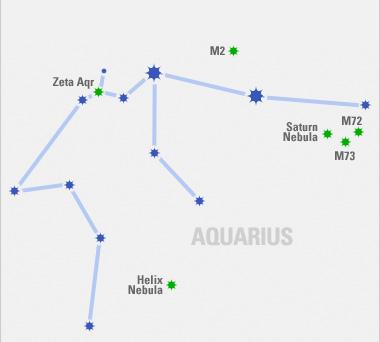

The Saturn Nebula (NGC 7009) is an oval Mag 8 fuzzy patch hanging in space about 4,000 lightyears distant. Medium-sized scopes show a ring with "knobs" on either side.

M72, close by, is a small remote globular cluster, difficult to resolve. The open cluster M73 is a tiny triangular collection of stars, barely noticeable. However, the same field of view contains a lovely Lyra-like asterism.

The Mag 7 globular cluster M2 is about 40,000 lightyears away. Although among the brightest of globs in the sky, M2's core is so concentrated that, as an observational object, it ranks as one of the less compelling.

The Helix Nebula (C63/NGC 7293) is a tricky target. Although it is the largest visible planetary in the night sky (about half the apparent diameter of the full moon) it's quite dim. Dark skies are a must. A low power eyepiece in your telescope, with averted vision, may give you some hint of structure.

Finally, 103 lightyears distant is one of the sky's finest doubles, Zeta Aquarius.

{ sourceURL:'/catalog/includes/quicklook_miniproduct.jsp?entityId=100334&entityTypeId=4', sourceSelector:'' }

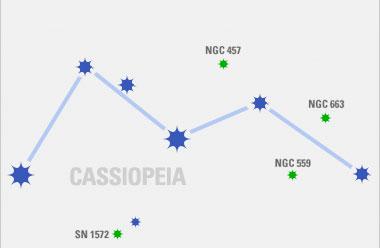

Cassiopeia is one of the easiest constellations to spot during the autumn and winter months; its big "W" shape rotates overhead each night. Apart from being a generally pretty area to scan in binoculars, there are some terrific sights to pick out.

9,000 light years away sits NGC 457, a 6th-mag open cluster known as the Owl Cluster. NGC 559 a 9.5-mag open cluster is about 2.5░ from NGC 663 a 7th-mag open cluster seen in binoculars.

Cassiopeia is also the area of sky where Tycho's Supernova of 1572 appeared slightly to the west of Kappa Cassiopeiae, changing the appearance of the sky for six months and cementing Copernicus' 1543 rebuttal of Ptolemaic theory; in that year Copernicus died and his great work De revolutionibus orbium coelestium was published, overturning the established doctrine that the Earth was at the center of the universe. Unfortunately, nothing is visible to amateur astronomers but the site is of obvious historic interest.

December 2005

{ sourceURL:'/catalog/includes/quicklook_miniproduct.jsp?entityId=100335&entityTypeId=4', sourceSelector:'' }

Auriga is most notable for its three bright open clusters and for sporting one of the ten brightest stars in the night sky, Capella.

In ascending order of interest are Auriga's three Messier-designated open clusters: M36, M38 and M37. All are clearly visible to the naked eye from a dark site and, in binoculars, appear as bright fuzzy patches; naturally, a telescope brings out the most detail. M36 will show around 50 stars in an 8" scope while M38 shows twice as many stars, some in apparent chain-like arrangements. But the most notable of the trio is M37. In a 12" scope, roughly 150 starts are visible in this neatly arranged cluster, some tinged red.

NGC 1931 is a bright emission nebula surrounding a very small open cluster. With high magnification in an 8" telescope, the nebula is quite apparent.

February 2006

{ sourceURL:'/catalog/includes/quicklook_miniproduct.jsp?entityId=100336&entityTypeId=4', sourceSelector:'' }

Eclipse Lore and Legend

Imagine living in a world without advanced astronomical reckoning. Imagine your world plunging into sudden darkness, the animals growing eerily silent. Imagine witnessing the sun, your source of warmth and life, being consumed by a swiftly encroaching shadow, leaving only a blinding hole in its wake.

The solar eclipse has always been seen as a powerful omen, variously ill and auspicious. This awesome sight has influenced wars, ended lives, made regular appearances in literature and, even with a modern comprehension of the forces at play, still holds a powerful hold over our collective imaginations. It is no wonder that the solar eclipse, which occurs only once in most life times, is the stuff of legend.

The history of the eclipse is divided between those who were able to predict its occurrence, and those who were taken by surprise. Though the tale may be apocryphal, the oft-repeated example of Columbus' manipulation of native Jamaicans is illustrative. The fellow apparently became stranded and ran out of supplies during his fourth trip to the new land, and he needed help. Rather than replenishing his resources, the inhospitable locals expressed their displeasure at his appearance by refusing sustenance and aid. It was only Columbus' ability to predict a fortunate lunar eclipse that saved him; announcing the great displeasure with which heavenly forces viewed the natives' reticence, Columbus claimed that the moon would be struck from the sky should the natives fail to assist him. How would the course of history have been affected, had the eclipse not come to pass?

Others have been less fortunate with their predictions. Advanced knowledge of the eclipse has been used to schedule important events, thereby "proving" their auspiciousness to the na´ve masses. However, when two early Chinese court astronomers failed to notify their Emperor of an upcoming solar eclipse circa 2000 BCE, they paid for it with their heads!

When eclipses occur unexpectedly, they have profound influence on world events. Take this tale of two wars; in 413 BCE a surprise eclipse convinced Athenian strategists of the Peloponnesian war that a planned retreat was ill advised. Delaying the move led to the easy slaughter of their troops; an early and unnecessary defeat at the hands of the Syracusans. Contrarily, in 585 BCE both the Lydians and the Medes saw the eclipse as evidence of heavenly displeasure with their years of war. In this instance, the magnificent sight inspired an early armistice and saved many lives.

This duality in our perception of the eclipse is apparent in world mythology, as well as in our history books. In many places, the disappearance of the sun is an alarming occurrence, attributed to mythical beasts (variously dragons, dogs, birds and demons) that come to consume our life-source. There is a widespread fear that, without intervention, the skies would be permanently darkened and life ever altered. It is only through scaring the Mongolian Sun Eater away with firecrackers, drumming and general cacophony that balance can be restored.

While this perception of eclipse as an ill omen is pervasive, there are also many cultures where the event is viewed positively. In Tahiti the eclipse is understood as the lovemaking of the Sun and Moon. Amazonian myth describes a passion so great between these lovers that the earth becomes scorched by the Sun's heat and drenched from the Moon's tears; to protect us from their excess, the two will only touch through the shadow of eclipse. This perceived concern for our well-being is reflected again in various Native American mythologies wherein the sun or moon absent themselves from the sky during an eclipse, to check that all is well on earth.

While there is often disparity between scientific understanding of the eclipse and mythological explanation, in Vedic tradition eclipse myth clearly demonstrates an accurate understanding of the principles at play. In this tale, the demon Rahu Ketu has come between the sun and moon to steal a sip of immortality nectar. Angered by this presumptuousness, Lord Visnu strikes the demon in half, separating head from body. As the demon was successful in procuring the heady libation, he is not killed but positions his two components at the north and south lunar nodes, ever after to seek vengeance on the two celestial bodies by swallowing them at the time of eclipse.

ę Sanskrit Religions Institute

The eclipse as a portent and harbinger of change is a common theme in history, literature and religion. The New Testament Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke all describe a solar eclipse during the crucifixion of Christ, causing his lament "My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?" Indeed, this use of eclipse as metaphor in classical texts has helped scholars to place events in historical context. We can, for example, compare Amos 8:9 of the Old Testament "and on that day, I will make the sun go down at noon, and darken the Earth in broad daylight" with Assyrian historical records, to conclude that "that day" occurred on June 15th, 763 BCE.

Shadow of the 1999 Total Solar Eclipse as Seen from Space

Our advanced astronomical understanding of eclipse phenomena has done nothing to diminish our fascination with the event. The convenience of modern travel now allows millions of spectators to flock to the path of totality for each occurrence. Perhaps there is something here of wonder; the only place in our solar system where the celestial bodies are of the necessary relative size and distance for complete obfuscation just happens to occur where there is life to appreciate the magnificence of the sight!

March 2006

Claire's long-time interest in mythology brings a different perspective to our understanding of the night sky.

{ sourceURL:'/catalog/includes/quicklook_miniproduct.jsp?entityId=100337&entityTypeId=4', sourceSelector:'' }

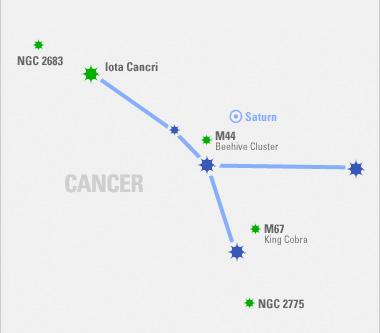

Lying quietly between Gemini and Leo, Cancer is not the most exciting of constellations. Nonetheless, it holds some modest riches worth checking out.

M44, the Beehive Cluster, is a great target for your binoculars or finderscope. More magnification than that and you'll loose the lovely sense of loose structure. Can you spot it naked eye? This month, M44 is easier to locate by eye, thanks to the presence of Saturn, shining a little to the West at Mag 0.

Even from your back yard 2,500 lightyears away, you should be able to scoop up M67 in your finderscope or binos. The individual stars of this Mag 6 open cluster will resolve nicely in your telescope's eyepiece.

NGC 2775 is a bright spiral galaxy whose core is visible in 8" scopes. Larger scopes will show hints of its spiral-arm structure. Spiral galaxies are the most common kind of galaxy, making up four fifths of all galaxy types, including our own galaxy, the Milky Way. And close by are two more galaxies, NGC 2777, a true gravitational companion of 2775, and NGC 2773 which is four times farther away from us but happens to lie along the same line of sight; you'll need a 10" scope to spot either.

At the opposite end of Cancer, Iota Cancri is a nice orange/green double star and well placed to point you just over Cancer's constellation boundary, into Lynx, where the edge-on 10th Mag galaxy NGC 2683 sits.

March 2006

{ sourceURL:'/catalog/includes/quicklook_miniproduct.jsp?entityId=100338&entityTypeId=4', sourceSelector:'' }

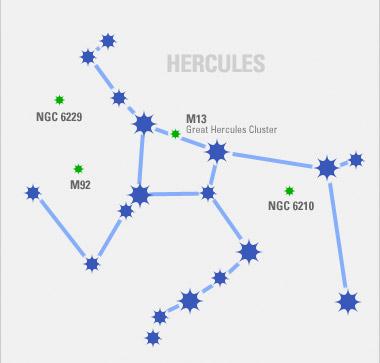

The fifth largest constellation in the sky, Hercules is perhaps most famous because of the Great Hercules Cluster, M13, perhaps the most prominent of globulars visible to northern hemisphere observers.

At least 149 globular clusters in the Milky Way have been discovered, and more than 100 are in the NGC-IC catalog. Their distribution forms a spherical halo, centered on the core of our Milky Way. "Globs" are densely packed balls of stars. Up to two million stars can be found bound together with a radius of no more than 100 light years.

The Great Hercules Cluster is visible to the naked eye at dark sites. The glob is about 14 billion years old and contains more than a million suns.

Because of its proximity to M13, M92 is often overlooked even though it's one of the brighter clusters available to northern viewers. One of Johann Elert Bode's discoveries in 1777, it was rediscovered by Charles Messier in 1781 and has been clocked speeding toward us at 112 km/sec.

NGC 6229 is another globular cluster that's worth a look. Mistaken for a nebula by Herschel in 1787, it was revealed to be a "very crowded cluster" in the mid 1800s.

NGC 6210 is a planetary nebula, a sun not unlike our own in the final stages of its life. It has a very high surface brightness and is a good target for high magnification.

July 2006

{ sourceURL:'/catalog/includes/quicklook_miniproduct.jsp?entityId=100341&entityTypeId=4', sourceSelector:'' }

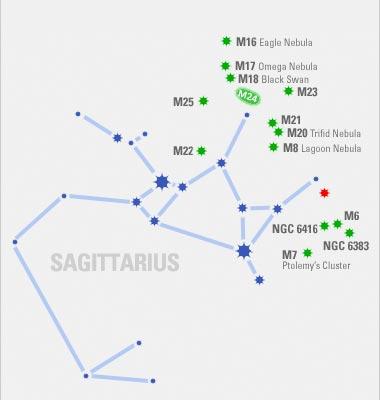

M6 and M7, two open clusters, are bright and obvious in Sagittarius, and make for easy binocular objects. Telescopes open up both in rich detail and M6 is seen to be aptly named "The Butterfly Cluster".

NGC 6416 is a small open cluster and NGC 6383 is a dim, wide cluster with nebulosity.

M8 "The Lagoon Nebula" is the brightest nebula after the great Orion nebula. It's actually more massive than M42 but is farther away: 4,500 light-years distant compared with 1,500 light-years. M8 is best viewed with a wide-field eyepiece. Less spectacular, but still worth some time, M20 "The Trifid Nebula" is also easily seen in binoculars; a telescope will bring out the dust band that gives the nebula is shape and name. M21 is a small rich open cluster in the same field of view as M20.

M23, excellent in small scopes, is an open cluster seen in binocs, as is M25.

M24 "Delle Caustiche" is a large and lovely "frothy" looking region seen easily in binoculars. It's actually part of the Milky Way and only stands out as a distinct patch because, like M23 and M25, it sits in front of a dark nebula that obscures our line of sight to the core of the galaxy. (By the way, the very center of our galaxy is marked above with a red target symbol.)

M22 is a sweet globular cluster, the third-brightest in the sky. Populated by half a million stars, it's distant by a mere 10,000 light-years, making it the nearest glob to Earth.

M16 and M17 are two nebulae, the latter in particular a rewarding target. M16, however, is notable for being the location of "The Pillars of Creation," the iconic image produced by the Hubble Space Telescope. M18 "The Black Swan" is a pretty open cluster with about 40 members, surrounded by fainter background stars in the band of the Milky Way.

August 2006

{ sourceURL:'/catalog/includes/quicklook_miniproduct.jsp?entityId=100342&entityTypeId=4', sourceSelector:'' }

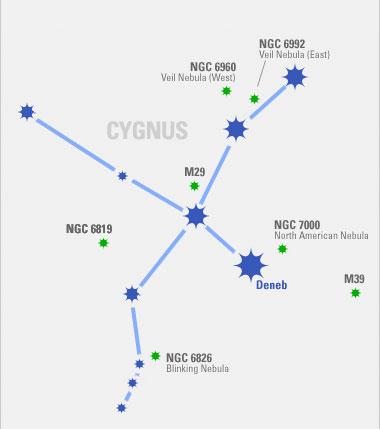

NGC 6960 & NGC 6992, the West and East Veil Nebulas, are part of the Cygnus loop, the remains of a supernova that exploded over 100,000 years ago. Two other sections, NGC 6995 and 6979 are close by.

M29 is an unimpressive open cluster, notable only in that it was one of the original discoveries of Charles Messier.

NGC 6819 is a small open cluster with about two dozen stars from 10th to 12th magnitude within a 5' circle. Its discovery in 1784 is attributed to Caroline Herschel.

Deneb, which marks the tail of the swan, is one of the 20 brightest stars in the night sky. Just three degrees away lies NGC 7000, the North American Nebula, so-called because of its obvious shape. This is an active star forming region and quite large, though it's difficult to see without the aid of astrophotography.

M39 is an open cluster, and is a nice binocular object with 30 or so stars spread over its seven lightyear diameter. It's also "pretty close" to Earth, at "just" 800 lightyears.

Finally, NCG 6826, the Blinking Nebula, gets its name from an odd phenomenon: its central star appears to blink on and off when you look toward and away from it quickly.

September 2006

{ sourceURL:'/catalog/includes/quicklook_miniproduct.jsp?entityId=100391&entityTypeId=4', sourceSelector:'' }

Triangulum is well placed at this time of year for observations of M33, a spiral galaxy. However, at 2.4 million light years and only 5% as massive as our own galaxy, it's a dim fuzzy object in 8" scopes and requires good dark skies to show any detail.

Follow a line from M33 through Mirach in Andromeda to find the brightest spiral in the sky, M31, the Andromeda Galaxy as well as its satellite galaxies M32 and M110. As with M33, the photons from M31 have travelled 2.4 million years to pass through the pupil of your eye and end their journey on your retina. The Andromeda Galaxy is also one of the few galaxies that's blue-shifted, meaning that is traveling toward us: almost all others are red-shifted and speeding away. Once you've found M31 with the aided eye, you can practice picking it out with the naked eye. You can then congratulate yourself that no-one can see any farther than you; the barely visible faint smudge you can just make out is the farthest object visible to the unaided eye.

At the tip of the constellation's brightest limb, is Almach (Gamma Andromedae) a very sweet orange/blue double. And finally, below Triangulum, in Aries, is Mesarthim (Gamma Aries) another lovely double, orange/green, sitting 207 light years away with an angular separation of 7.5".

October 2006

{ sourceURL:'/catalog/includes/quicklook_miniproduct.jsp?entityId=100397&entityTypeId=4', sourceSelector:'' }

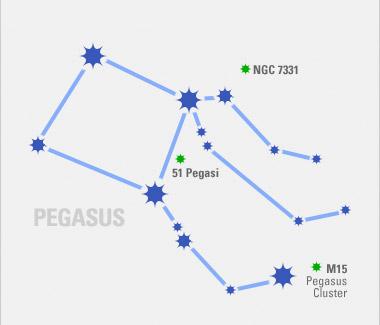

M15 is one of the most densely packed globular clusters in our galaxy, with a high number of variable stars and pulsars. Viewable with the naked eye from dark sites, binoculars and small scopes will bring out some detail of the collapsed, superdense core. M15 is also one of only a handful of globular clusters known to contain a planetary nebula.

NGC 7331, a Type 2 Seyfert galaxy about 43 million light-years away, shows a superb spiral structure.

51 Pegasi is an unexceptional 8th Mag star, but it's notable because it is orbited by the first true extrasolar planet to have been discovered.

November 2006

{ sourceURL:'/catalog/includes/quicklook_miniproduct.jsp?entityId=100399&entityTypeId=4', sourceSelector:'' }

For those of us who live in northern climes, winter astronomy is a mixed blessing. Some of the finest objects in the sky are best placed in winter time, but the cold weather often keeps us from enjoying them. In this article I'll give some tips for winter observing, and then highlight some of the sights that will make it worth braving the cold.

Preparing yourself

Crisp winter days can be enjoyable when the Sun shines brightly and you can walk/ski/snowshoe briskly. It's a different matter standing or sitting very still peering through an eyepiece under a winter night sky. The first thing to do is to dress warmly, in layers, in order to retain your body heat. Because astronomy doesn't involve much physical movement, you should dress as if the temperature was at least 10 degrees colder than predicted. The clothing sold for other winter outdoor activities serves very well. I recently discovered jeans lined with flannel at a work clothing store, which serve well on milder nights; I have a fully insulated one-piece boiler suit for really cold nights. A warm hat is especially important, as we lose much of our body heat through our head: I usually wear a wool watch cap. On really cold nights, a ski mask or balaclava is really welcome. It's also important to keep your feet warm: cold feet will kill your observing interest faster than anything else. Insulated working boots will do the trick, but it also helps if you put down an insulating mat under your observing area.

There are some serious safety concerns in winter observing. Hypothermia can creep up on you very subtly. If you?re observing from a remote location, always use the buddy system, and make sure your buddy has his own car, in case you have trouble starting yours. I prefer observing close to home, where I can step inside every hour or so to warm myself up. Be very careful around the metal parts of your telescope: it's extremely easy to freeze your flesh to any exposed metal parts of the scope. If it happens, warm things gradually and separate with great care. A warm beverage in a thermos can help to keep you comfortable, but avoid caffeine and especially alcohol.

Preparing your telescope

Most telescopes are manufactured in parts of the world warmer than where we live. The only telescope I own which seems really happy in winter is my Russian-made Maksutov-Newtonian, which seems to feel right at home at sub zero temperatures! Telescopes give trouble in two specific areas: lubrication and batteries. The lubricants used in telescope mounts, focusers, etc. turn into glue at low temperatures. It's best to strip off the supplied lubricant and replace it with the lithium-based greases designed for snowmobiles.

Batteries depend on chemical reactions to generate current, and chemical reactions go more slowly at lower temperatures. Generally, the smaller the size of the battery, the sooner it will fail at cold temperatures. I often store my telescopes in an unheated garage or shed, but I always store the batteries inside my heated house. The little AA and 9v cells used in most astro equipment are next to useless below freezing. If you?re close to home, use an AC adapter to power your equipment. If you?re in the field, look into the "power tanks" sold by many astronomical suppliers. But before spending a lot of money on one of these, check your local auto supply store for less expensive alternatives. Once again, the larger the physical size of the battery, the longer it will last, and be sure to store it indoors on a trickle charger. It may be tempting to run your equipment off your car?s battery, but you don't want to find yourself with a dead battery when you want to head home.

It's best to store your telescope in an unheated garage or shed, rather than subjecting your scope to drastic temperature changes, plus the heavy condensation which can occur when you bring the scope indoors. If you must bring a very cold scope indoors, cap it tightly while still outside to minimize internal condensation. The same applies to eyepieces and other accessories.

The Rewards!

Is it worth going to all this trouble, rather than staying indoors and viewing Hubble images on the internet? Definitely! Some of the sky's finest sights are overhead in wintertime.

The Orion Nebula (Messier 42 and 43)

The Orion Nebula (Messier 42 and 43)

This is without argument the finest emission nebula in the sky. It is easily found as the middle "star" of the Sword of Orion, hanging below his famous Belt. This is a fantastic site in even the smallest telescope, and only gets better the larger your telescope's aperture and the darker your sky. Try it with every eyepiece you own, with and without a nebula filter. Every view is different, and every one rewarding. I can easily spend an hour or two exploring this wonderful object on any clear night. Try to trace the outermost tendrils of its two widespread arms. Then put on your highest magnification and see how many stars you can see in The Trapezium, the glorious multiple star at its core.

The four brightest stars are pretty easy, but can you spot the elusive fifth and sixth stars? These require good optics and a dark sky, as they are buried in the glow of the surrounding gasses.

Rigel

This is one of my very favorite double stars. I discovered it quite by accident one night when I was testing a new telescope. I was looking for a bright star to use for a star test, and chose Rigel. When I cranked up the magnification, I was amazed to discover than Rigel was not alone, but had a tiny white speck of a companion. Though actually a white dwarf, this star gives the impression of a tiny planet circling a brilliant star. This discovery started me on a quest to observe double stars, for which I used the wonderful list of a hundred doubles recommended by the Astronomical League:

http://www.astroleague.org/al/obsclubs/dblstar/dblstar1.html

Double star observing used to be a mainstay of amateur astronomy, but got shoved aside by deep sky observing for many years. Recently it seems to be enjoying a comeback with several new books published on the subject.

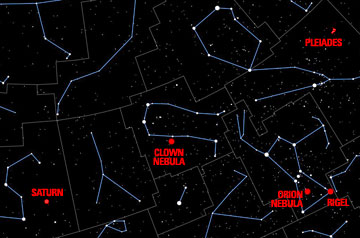

Eskimo or Clown Nebula (NGC 2392)

Summer may have its Ring Nebula and Dumbbell Nebula, but winter's Eskimo Nebula will challenge both of these as the finest planetary nebula in the sky. Located close to the fine double star Wasat (Delta Geminorum), it is easily mistaken for a star at low power because of its small size and brightness.

The Pleiades (Messier 45)

The brightest and one of the closest open star clusters in our neighborhood, The Pleiades makes a fine sight on a crisp winter night. How many stars can you see with your naked eye? Most people can see six, but more can be detected with careful observation. Because of its large size, this cluster is best viewed with binoculars. Under really dark skies, see if you can detect the faint nebulosity which envelopes this cluster. Don't be fooled by haze in our own atmosphere. A good test is to compare the view with the nearby Hyades, which have absolutely no nebulosity associated with them.

Saturn

I saved the best for last! Saturn is now rising in the mid-evening, and is a treat for all astronomers. This planet can tolerate as much magnification as your telescope is capable of, so don't hold back. Look for the shadow of the rings on the planet and vice versa. See if you can detect the hairline Cassini division between the two main rings; how far around the ring can you follow it? Try to spot the faint inner Crepe Ring, most easily seen against the background of the planet, but sometimes visible against the sky. Can you see any belts on the globe, or its greenish polar region? Scan the area around Saturn for its moons. Use Starry Night« to print a map of their locations. Titan is easily seen in any telescope. Rhea is more of a challenge and Tethys and Dione require a good eye and telescope. Iapetus follows an odd orbit, and changes in brightness as it moves from west to east. Enceladus is extremely challenging, and tiny Mimas just about impossible.

So remember: Dress warmly, be prepared, and enjoy the wonderful sights of the winter sky!

January 2007

Geoff has been a life-long telescope addict, and is active in many areas of visual observation; he is a moderator of the Yahoo "Talking Telescopes" group.

{ sourceURL:'/catalog/includes/quicklook_miniproduct.jsp?entityId=100403&entityTypeId=4', sourceSelector:'' }

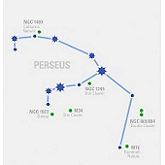

Perseus is the mythological hero who saved Andromeda from Cetus, the Sea Monster. Perseus used Medusa's head (lopped off in a previous adventure) to turn Cetus to stone. At this time of year Perseus is visible in the north-east after dusk. As the night progresses, it rises higher for excellent viewing, and there are a number of fabulous sights on show...

NGC 869/884, the Double Cluster, is a favorite target and with good reason. Use binoculars to get an overview of this jewel box, then a low magnification in your telescope to bring out the distinctly varied coloration of stars in each cluster. Both clusters are about 7000 light-years away and are part of the Perseus arm, one of the spiral arms of our Milky Way.

M76, the Dumbbell Nebula, is another favorite among observers because of its obvious hourglass/dumbbell shape. It's faint and small but responds well to magnification. Averted vision will help you see its two distinct lobes and nebulous wisps.

NGC 1245, an open cluster, is best viewed with low magnification. Most of the stars are hot blue, but there are some nicely contrasting bright orange stars, cooler and older than their blue house mates.

M34, another star cluster, contains about 60 members including several double-stars. The cluster is 1,500 light-years distant and is moving in the same direction through space as the Pleiades.

NGC 1023, an very elongated looking galaxy, hangs in space roughly 30 million light-years from the back of your eye. From that distance it's surprisingly bright, especially the middle. Try all magnifications to pick out structure and details.

NGC 1499, the California Nebula, is a large emission nebula. Under dark skies, it's bright enough to see with the naked eye. Use low magnification and a nebula filter if you have one. See if you can make out the shape of the state that gives the nebula its name.

January 2007

{ sourceURL:'/catalog/includes/quicklook_miniproduct.jsp?entityId=100404&entityTypeId=4', sourceSelector:'' }

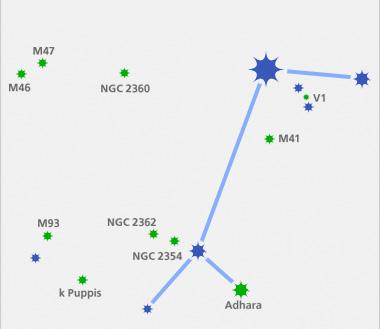

At Mag -1.5, almost everyone knows that Sirius is the brightest star in the night sky. You may notice it driving home from work: visible from early dusk, it sparkles brilliantly above the southern horizon. What many people don't realize is that Sirius is actually a double star. Sirius B is a challenging target, just 5" from Sirius and quite dim at Mag 8.5. It requires excellent optics but, if you can nail it, it's surely a feather in your cap.

A little to the west of Sirius is a three star asterism, with the central star, V1, being an easy, pretty double separated by 17".

M41 (also known as the Little Beehive) is a fine open cluster lying about 2,000 lightyears from the back of your eyeball. It has about 25 bright stars spattered across a field about the size of a full moon; in reality, they're spread over an area 20 lightyears in width. Bright enough to be sometimes visible to the naked eye (Aristotle is said to have noticed it around 325 B.C.) M41 is a good target for binos or low magnification in your scope.

M46 and M47 are two open clusters just over 1░ apart, making comparison very easy. Both are about 20 million years old but they're not connected in any way: M46 hangs in space about 5,000 lightyears distant, while M47 is closer at 1,700 lightyears. Of special interest is the planetary nebula that seems to be embedded near M46's center. Although the nebula is probably not actually part of the cluster (it simply lies along the same line of sight), it makes for a good opportunity to see two different types of deep sky object at the same time.

In larger scopes, NGC 2360 (a.k.a. Caldwell 58) is a pleasing open cluster almost half way between M46 and Sirius.

M93, the winter Butterfly Cluster, is a rich 6th Mag open cluster with about 80 visible stars. It's core resembles an arrowhead. While you're in the area take a look at k Puppis, a nice bright double.

NGC 2362, the Mexican Jumping Star (a.k.a. Caldwell 64), and NGC 2354 are another pair of closely placed open clusters worth comparing.

Finally, Mag 1.5 Adhara has a Mag 7.5 double just 7.5" due south. Adhara is a main sequence star that shines 9,000 times as brightly as our own sun. Good thing it's 432 lightyears away.

February 2007

{ sourceURL:'/catalog/includes/quicklook_miniproduct.jsp?entityId=100405&entityTypeId=4', sourceSelector:'' }

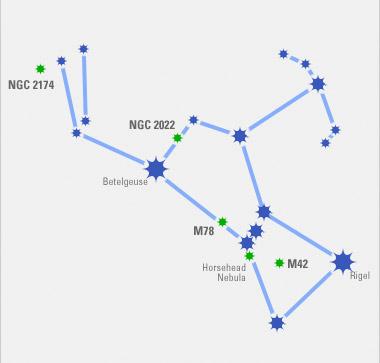

Visible towards the southern horizon from winter through spring in the northern hemisphere, Orion is one of the most easily recognizable and beloved constellations.

By far, the most popular celestial gem in the constellation of Orion is M42, The Great Orion Nebula. Although it is 1500 light-years away, M42 is a great target to view in small telescopes. This is due not only to its brightness, but also to its wonderful cloud structure, which in telescopes takes on a clearly three-dimensional shape.

Observers new and old come back to M42 time and time again because of the wealth of detail visible: pinpoint stars hang among uncanny, ghostly tendrils of glowing hydrogen that stream across space for trillions of miles.

Astronomers call M42 a stellar nursery; when you look at this giant gas cloud you are seeing what our own solar system might have looked like billions of years ago. The nebula's reddish coloration (visible only in photographs) betrays the ionized hydrogen that predominates the composition of the cloud, but carbon monoxide and other complex molecules have also been detected. When viewed through a large telescope, the cloud takes on a wonderful greenish hue.

The energy that keeps the nebula glowing so bright comes from the very hot, young stars in the brightest part of the cloud. Known as the Trapezium, this formation of four stars (from west to east: A, B, C, and D) is visible in most backyard telescopes.

A fun challenge for amateur astronomers is to "bag" the two 11th magnitude E and F stars, shown here in green. Their proximity to far brighter stars makes them difficult to separate on nights of so-so seeing. On great nights, discerning the E and F stars is a good test of your telescope's optics.

More Targets

The Horsehead Nebula was made famous from its beautiful photographs; it really does resemble what its name implies! The Horsehead can be found just below Alnitak (the leftmost/easternmost star in Orion's belt). The Horsehead is an extremely difficult target for medium aperture telescopes, and requires steady and dark skies to be seen even in a larger telescope.

A far easier nebular target in the same area can be found above Alnitak: Located above Orion's belt, M78 belongs to the same large cloud of gas and dust as the main Orion nebula (M42). It has 2 companion nebulae (NGC 2067 & 2071). All 3 are reflection nebulae, and M78 is in fact the brightest reflection nebula. It is visible in binoculars but best seen through a telescope.

NGC 2022 is a bright planetary nebula: a dying sun peeling off its outer shell. Because planetary nebulae are best viewed at high magnification, you should start out low (40x) to find the object, and then try 100x and 200x. The name "planetary" is misleading, as these objects are not planets at all but stars at the end of their life cycle. However, they do look something like cloudy planets, and this fact confused earlier observers whose incorrect naming convention has stayed with us to this day.

NCG 2174 is a bright but diffuse emission nebula, a cloud of hydrogen gas very close to a young hot star (or multiple stars). In such clouds, energy from the stars heats up the hydrogen to 10,000░K until it glows with the distinctive red color one can see in long-exposure photographs.

Betelgeuse is the only red star in Orion. Not only does this make it easy to identify, it also tells us we are looking at a giant star.

Betelgeuse (pronounced beetle juice by most astronomers) derives its name from an Arabic phrase meaning "the armpit of the central one."

The star marks the eastern shoulder of mighty Orion, the Hunter. Another name for Betelgeuse is Alpha Orionis, indicating it is the brightest star in the winter constellation of Orion. However, Rigel (Beta Orionis) is actually brighter. The misclassification happened because Betelgeuse is a variable star (a star that changes brightness over time) and it might have been brighter than Rigel when Johannes Bayer originally categorized it.

Betelgeuse is an M1 red supergiant, 650 times the diameter and about 15 times the mass of the Sun. If Betelgeuse were to replace the Sun, planets out to the orbit of Mars would be engulfed!

Betelgeuse is an ancient star approaching the end of its life cycle. Because of its mass it might fuse elements all the way to iron and blow up as a supernova that would be as bright as the crescent Moon, as seen from Earth. A dense neutron star would be left behind. The other alternative is that it might evolve into a rare neon-oxygen dwarf.

Betelgeuse was the first star to have its surface directly imaged, a feat accomplished in 1996 with the Hubble Space Telescope.

On the western heel of Orion, the Hunter, rests brilliant Rigel. In classical mythology, Rigel marks the spot where Scorpio, the Scorpion stung Orion after a brief and fierce battle. Its Arabic name means the Foot.

Rigel is a multiple star system. The brighter component, Rigel A, is a blue super giant that shines a remarkable 40,000 times stronger than the Sun! Although 775 light-years distant, its light shines bright in our evening skies, at magnitude 0.12.

Telescope observers should be able to resolve Rigel's companion, a fairly bright 7th magnitude star.

A heavy star of 17 solar masses, Rigel is likely to go out with a bang some day, or it might become a rare oxygen-neon white dwarf.

Don't forget to compare the colors of Betelgeuse and Rigel on your next outing under the stars!

March 2007

{ sourceURL:'/catalog/includes/quicklook_miniproduct.jsp?entityId=100409&entityTypeId=4', sourceSelector:'' }

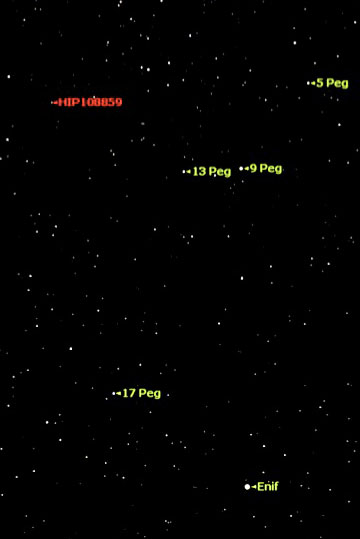

The first confirmed discovery of a planet revolving around a star other than the Sun was made less than 30 years ago by Canadian astronomers Bruce Campbell, G. A. H. Walker, and S. Yang. Since then, more than 200 more so-called exoplanets have been discovered. Most of the stars with known planets are fairly faint, and known mainly by their catalog number.

One of the most interesting has been the planet HD209458b, which revolves around the 8th magnitude star HD209458 in the constellation Pegasus. This planet, nicknamed Osiris after the Egyptian god, was discovered in 1999, and was the first known exoplanet to transit its star regularly. In other words, its orbit is such that the planet passes between us and its star once a "year," its year being 3.5 Earth days long. Its spectrum has been studied by the Hubble Space Telescope, and is known to contain water.

Like all stars except the Sun, HD209458 is too far away to show a disk, appearing in the largest telescopes as a point of light. But, simply because it?s known that this star has a planet with water, there is a real fascination of seeing it with our own eyes and, with the help of Starry Night« and a small telescope, this is quite possible.

HD209458 is also known as HIP108859, and it is under that catalog number that you can find it in Starry Night. It is visible at present in the morning sky, between the stars 9 and 33 Pegasi in one of the "legs" of the winged horse Pegasus. You can find it easily by starting at the bright star Enif, Epsilon Pegasi. Sweep 7 degrees north to find 9 Pegasi, 4th magnitude. Look for 5th magnitude 13 Pegasi a little over a degree east of 9 Pegasi. From there, HIP108859 is 3.5 degrees northeast. This star is very similar in size and color to our Sun, but is located 154 light years away.

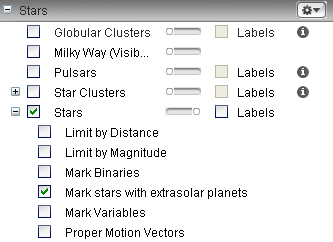

How to Mark Stars With Extrasolar Planets

Starry Night« Tip for Pro and Pro Plus version 6 users

- Open the Options Pane and expand the Star Options Layer.

- Check the "Mark Stars with Extrasolar Planets" box.

- Circles will appear around the stars that are known to harbor planets.

- If you turn on markers for extrasolar planets, the star's Info pane will include information about the extrasolar planet, such as the planet?s mass and distance from its central star.

May 2007

Geoff has been a life-long telescope addict, and is active in many areas of visual observation; he is a moderator of the Yahoo "Talking Telescopes" group.

{ sourceURL:'/catalog/includes/quicklook_miniproduct.jsp?entityId=100415&entityTypeId=4', sourceSelector:'' }

Lyra is currently well placed for observation. Overhead during and after dusk, it passes through the zenith around midnight.

Vega is the northern hemispehere's second brightest star; only Sirius, at a magnitude of -1.5, is brighter. Because the Earth's spin is slightly imperfect, its axis carves a circle on the sky every 26,000 years. The phenomenon, called precession, means that as time progresses each pole, north and south, points to different stars. 13,000 years ago, Lyra was directly above our north pole and therefore acted as our Pole Star. And in another 13,000 years or so, it will once again act in that capacity.

One of the best known planetary nebulas is M57, lying roughly half way between Sheliak and Sulafat. Its cosmic bagel structure is apparent even in a 3" scope and, with larger apertures, only becomes clearer and more detailed. Try several levels of magnification.

M56 is a fairly dispersed globular cluster.

Finally, Epsilon Lyrae is one of the most beloved double star systems. It's fairly easy to split the first double, but higher magnification reveals that each component is itself a binary system.

August 2007

{ sourceURL:'/catalog/includes/quicklook_miniproduct.jsp?entityId=100425&entityTypeId=4', sourceSelector:'' }

Gemini is well placed for observations in December, floating high overhead in the south-east by late evening.

Castor is an easy, pretty double which resolves nicely in small scopes. A true double, the stars revolve around each other every 510 years.

Close by is NGC 2372, a faint planetary nebula that looks like a mini-dumbbell.

The Eskimo Nebula (NGC 2392), photographed so magnificently by the Hubble Space Telescope, is also known the Clown Face Nebula. Only large scopes bring out the details you would associate with a face, but it's a fun target nonetheless.

M35 (NGC 2168) is a lovely open cluster by Gemini's left foot, with a smaller, dimmer but rich companion cluster NGC 2158; physically unrelated, they just happen to lie along the same line of sight.

December 2007

{ sourceURL:'/catalog/includes/quicklook_miniproduct.jsp?entityId=100430&entityTypeId=4', sourceSelector:'' }

Don't let the scale of the diagram above fool you: Hydra is the largest constellation, and covers some 90░ of sky. At this time of year, from mid-northern latitudes, it lies along the southern horizon at midnight.

To start, M83 is an impressive barred spiral galaxy that, from our vantage point in space, lies almost face-on. Even small scopes should pick up its obvious structure.

M68 is a nice globular cluster, 33,000 lightyears away. It's visible in binoculars but a telescope brings out the individual suns.

NGC 3242, the Ghost of Jupiter, is one of the finest planetary nebulae in the sky. It's a full magnitude brighter than the more famous Ring Nebula (M57) in Lyra. A small telescope reveals a pale blue disc with diffuse edges and the prominent 11th magnitude star. Due to its high surface brightness, this target takes high magnification quite well: try 200x or 250x to see the football-shaped interior and faint shell.

NGC 3115, the Spindle Galaxy, is actually in Sextans. In contrast to M83, this galaxy is seen almost edge on. It's a lenticular galaxy, meaning it's a disc galaxy with very little spiral structure.

April 2006

{ sourceURL:'/catalog/includes/quicklook_miniproduct.jsp?entityId=100339&entityTypeId=4', sourceSelector:'' }

{"showSinglePage":false,"totalItems":263,"defaultPageSize":20,"paging_next":"Next","paging_view_all":"View All 263 Items","paging_view_by_page":"View By Page","pageSize":20,"paging_previous":"Prev","currentIndex":220,"inactiveBuffer":2,"viewModeBeforePages":true,"persistentStorage":"true","showXofYLabel":false,"widgetClass":"CollapsingPagingWidget","activeBuffer":2,"triggerPageChanged":false,"defaultTotalItems":263}

Why Buy From Orion

- 30 Day Money Back Guarantee

- Safe & Secure Shopping

- Next Day Shipping

- Easy Returns

- Sale Price Guarantee

- Free Technical Support

Shop Our Catalogs

Check out our colorful catalog, filled with hundreds of quality products.

See our eCatalogsEmail Sign Up

- 800-447-1001

- Telescope.com

- © 2002- Orion Telescopes & Binoculars All rights reserved

- DMCA/Copyright

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy & Security

About Orion Telescopes & Binoculars

Since 1975 Orion Telescopes & Binoculars has been offering telescopes for sale direct to customers. Now an employee-owned company, we pride ourselves on an unswerving commitment to best quality products, value and unmatched customer care. Our 100% satisfaction guarantee says it all.

Orion offers telescopes for every level: Beginner, Intermediate, Advanced, and Expert. From our entry level beginner telescopes for amateur astronomers to our Dobsonian telescopes to our most advanced Cassegrain telescopes and accessories, you can find the best telescope for you. Because we sell direct, we can offer you tremendous value at a great price. Not sure how to choose a telescope? Orion's Telescope Buyer's Guide is a great place to start.

Orion binoculars are known for quality optics at a great price. We offer binoculars for every viewing interest, including astronomical binoculars, compact binoculars, waterproof binoculars, birding binoculars, and sport and hunting binoculars.

Orion's telescope and astrophotography accessories will enhance your telescope enjoyment without breaking the bank. Expand your viewing experience with accessories ranging from moon filters to power-boosting Barlow lenses to advanced computerized telescope mounts. Capture breathtaking photos with our affordable astrophotography cameras. And when you're stargazing, Orion's telescope cases and covers, observing gear, red LED flashlights, astronomy books and star charts will make your observing sessions more convenient, comfortable and meaningful.

At Orion, we are committed to sharing our knowledge and passion for astronomy and astrophotography with the amateur astronomy community. Visit the Orion Community Center for in-depth information on telescopes, binoculars, and astrophotography. You can find astrophotography "how to" tips and share your best astronomy pictures here. Submit astronomy articles, events, & reviews, and even become a featured Orion customer!

sales, new products, and astronomy.